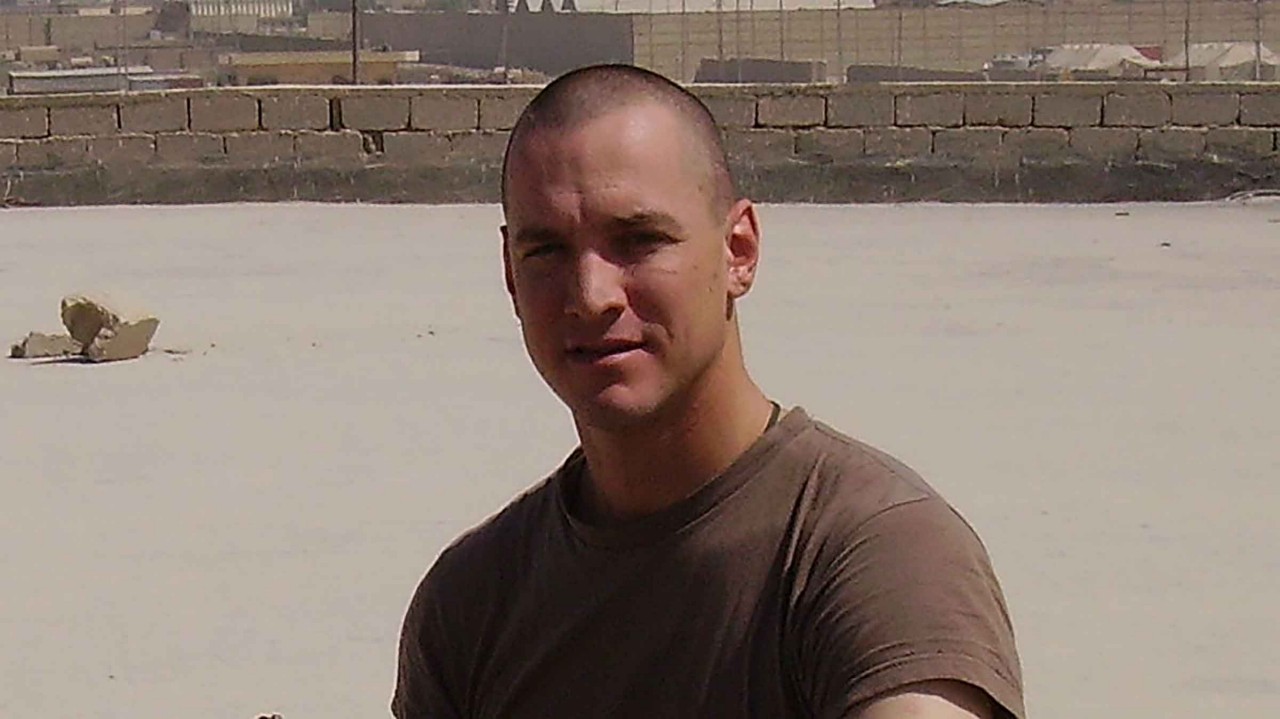

Iraq War veteran, advocate supports those who served

Patrick Ziegert will never forget June 5, 2005. As a cavalry scout in the army, he was stationed in southern Baghdad when his group got caught in an ambush. Three of his close friends lost their lives that day.

“Luckily, I got out OK,” he said, before pausing. “Physically intact, at least.”

When he came back home, it was a difficult transition.

“I realized I wasn’t the person I thought I was going to be,” Patrick said. “I had anger issues. I was suffering from all of the symptoms you could imagine from post-traumatic stress but I didn’t get a diagnosis for a while.”

The clinician who eventually diagnosed Patrick with PTSD was not with the military, but a civilian. And he was able to start getting the help he needed.

“It was great,” Patrick said. “At least I knew what was going on. I could put a name to what I was suffering through. It felt good understanding the different recovery techniques. And how I could probably help others so they wouldn’t have to follow on the path of most resistance.”

Patrick is now a veterans’ advocate for UHC Community & State based in Arizona, helping those who served and their families get the help and services they need. The path from that day in 2005 to now has been a long one, but his experience has given him insights into the challenges the military community can face, particularly with behavioral health issues.

According to a recent study by the Department of Veterans Affairs, about 20 veterans die by suicide every day. PTSD affects about 1 in 10 Afghanistan veterans and as many as 1 in 5 Iraq War veterans. Although many veterans may reintegrate back into civilian life without any problems, barriers to access can make getting the care they need more difficult than it has to be.

“Many veterans are accessing care in our local communities,” said Patty Horoho, former Surgeon General of the Army and current CEO of OptumServe, which provides health services and expertise to federal agencies. “It is critically important that these care providers understand the unique health needs of our veteran population to ensure high quality outcomes and the very best experience.”

The military has a distinct culture that, from the outside, might be hard to understand. When clinicians, social service providers, and other community members understand that culture better, they can help break down those barriers so veterans can have healthier lives.

With that in mind, here are some things Patrick thinks people should know, based on best practices, to have a supportive conversation with those who served.

Consider who is a veteran

Being a veteran is a wide-ranging category, depending on who you ask. But not everyone who is a veteran considers themselves one. This can be for a variety of reasons, such as discharge status, not deploying or serving in combat, or being on active duty, or in the reserve or the National Guard. Also women are less likely to self-identify as veterans than men. It’s important not to make assumptions about what a veteran should look like, or how they should act. Asking “have you ever served in the military?” rather than “are you a veteran?” can open a lot more doors.

Be honest

If you don’t know something, ask. Many may be very proud to share their experiences. Acknowledge a person’s service by asking what branch they were in and their job.

Be sensitive with your questions

Asking “have you ever killed anyone?” can be deeply hurtful. Instead ask: “What was your worst day in the military?” and then follow it up with “what was your best day in the military?” Military service is often complex, with both good and bad experiences.

Know that first impressions are crucial

Sometimes it can be hard for veterans to ask for help. “You put the mission first. For some people that doesn’t seem to include themselves,” Patrick said. “There’s sometimes an expectation that if you’re not operating perfectly then there’s something wrong with you.” This is why a positive first impression is so important. “If we do have a bad experience (for example, with a provider) we may not ask for help again. And a lot of folks just need that encouragement.”

Understand the importance of family

For many veterans, their families “serve with them,” with experiences that carry their own emotional weight. In Arizona, for example, a 2017 statewide survey of veterans found that 39% of veterans have minor children in the home. Of those, 27% have kids who have been diagnosed with a mental health disability or condition.

“When we answer the call to serve our country, our families also serve and make incredible sacrifices,” noted Horoho, who is also a nurse. “Having the right support systems within the community, including the health care system, is vital to properly address the overall health and well-being of service members and their families.”

There are many resources if you want to know more about the best ways to support those who served. The PsychArmor Institute uses best practices to engage with veterans and their families in an effective, compassionate way. All of their trainings are free, and they provide full courses for employers, providers, educations, and many other groups.

If you need to talk to someone, the Veterans Crisis Line from the Department of Veterans Affairs is a 24/7 resource for veterans, spouses and friends and family. Call 1-800-273-8255 / TTY 711 option 1, or text “838255.”